Carry Trades and The Failure of Macro Economics:

The Yen and Dollar Carry Trades, and The Creation of the World As We Know It Today.

1/28/2016

Carry Trades

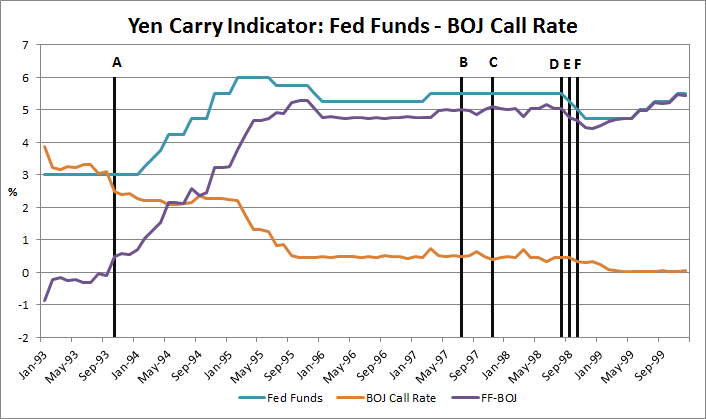

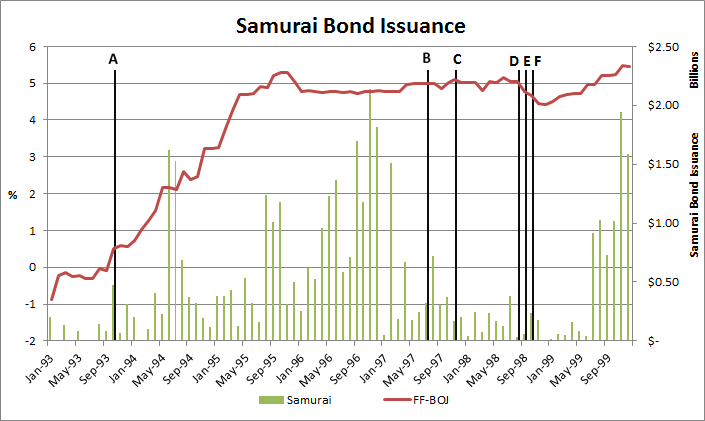

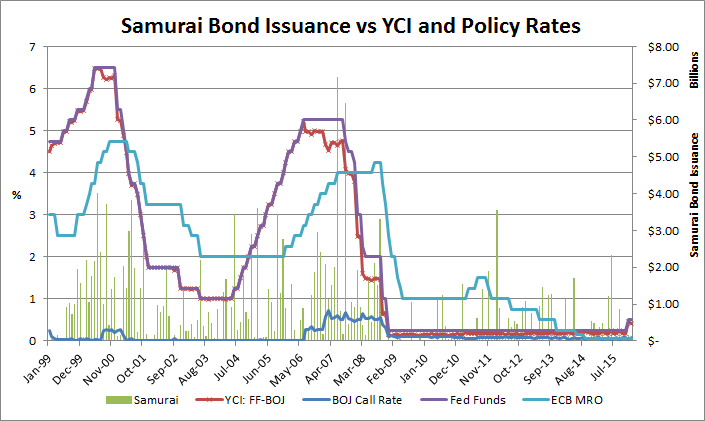

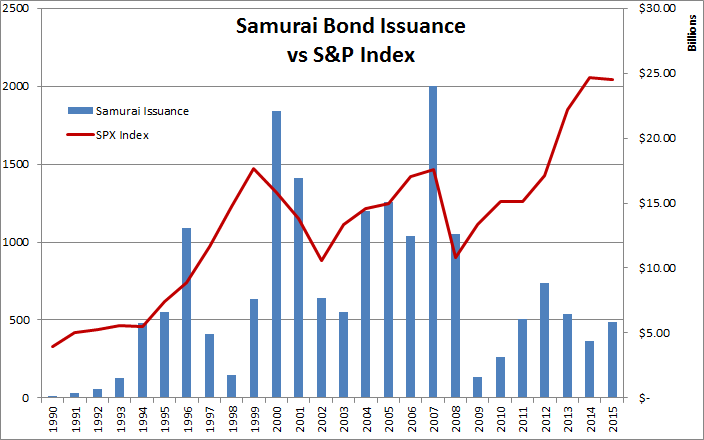

Initial Funding of the Yen Carry Trade was through Samurai Bonds

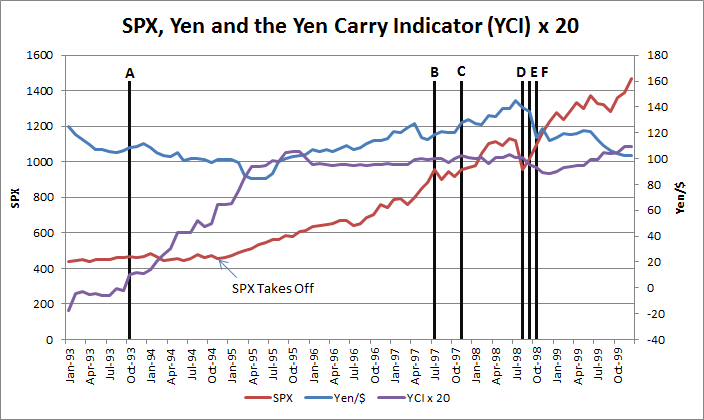

Tiger Management, until recently the largest such fund in the world. In its heyday in the summer of 1998, Tiger had more than $20 billion under management, considerably more than George Soros' Quantum Fund, and was reputed to be even more aggressive than Quantum in making plays against troubled economies. Notably, Tiger was perhaps the biggest player in the yen "carry trade"--borrowing yen and investing the proceeds in dollars--and its short position in the yen put it in a position to benefit from troubles throughout Asia. But when the yen abruptly strengthened in the last few months of 1998, Tiger lost heavily--more than $2 billion on one day in October--and investors began pulling out. The losses continued in 1999--from January to the end of September Tiger lost 23 percent, compared with a gain of 5 percent for the average S&P 500 stock. By the end of September, between losses and withdrawals, Tiger was down to a mere $8 billion under management.

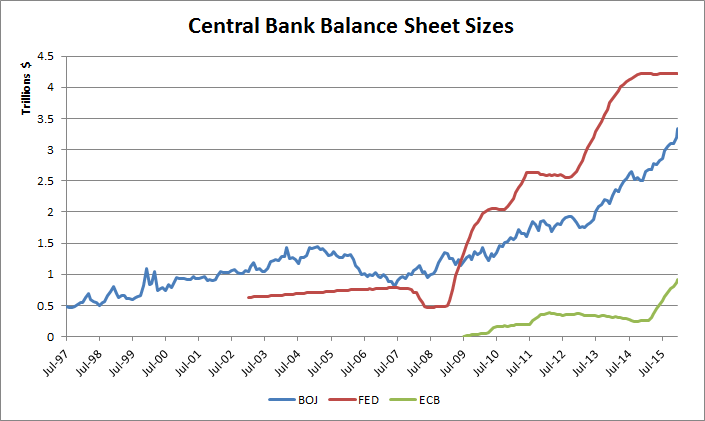

Quantitative Easing (QE) and Central Bank Balance Sheets

Wikipedia has a good definition, so I will use it:

Quantitative easing (QE) is a monetary policy used by central banks to stimulate the economy when standard monetary policy has become ineffective. A central bank implements quantitative easing by buying financial asets from commercial banks and other financial institutions, thus raising the prices of those financial assets and lowering their yield, while simultaneously increasing the money supply.

When US QE was implemented, I discussed why QE cannot work, in the section called 'Bonds are not Assets' in the 2009 Crisis Note 'Excess Assets, Keynes, etc'. However, QE can increase the money supply by the amount of bonds purchased (similar to an addon wing on a car increasing downforce by the amount of it's weight). Without velocity of money, however, this is a pointless exercise, unless the goal is to enrichen banks.

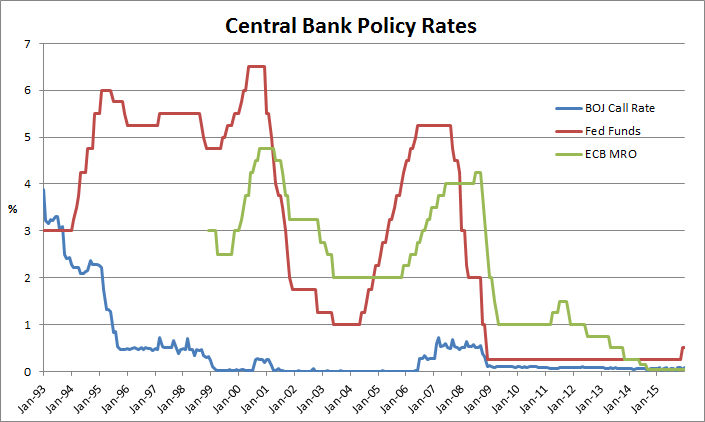

All three major central banks have resorted to QE, at different points in time, after entering Liquidity Traps. The extent of QE that they have implemented can be measured by the size of their (ballooning) balance sheets. The following chart shows the magnitude of their balance sheets (in USD). Combined, they currently total $8.5T, of which approximately $7.5T is as a result of QE.

Money Supply

- Central banks choose the price (rate) at which they lend high powered money to the private sector.

- This official rate is transmitted to other market rates via the banking system to varying degrees, and impacts assets prices and expectations, as well as the exchange rate.

- These changes in turn effect spending, savings, and investment behavior, which impacts the demand for goods and services.

- Monetary policy works via its influence on aggregate demand in the economy. Monetary policy thus determines the general price level, and the value of money ie the purchasing power of money. (Inflation is thus a monetary phenomenon. )

- Changes in the policy rate lead to changes in behavior of both individuals and firms, which when added up over the whole economy generate changes in aggregate spending.

- Total domestic expenditure in the economy is equal to the sum of private consumption expenditure, government consumption expenditure and investment spending. This, plus the balance of trade (net exports) is equal to GDP.

- Monetary policy changes affect output and inflation, as well as inflation expectations. - Inflation expectations influence the level of real interest rates and so determine the impact of any specific nominal interest rate. They also influence price and money wage setting, and so feed into actual inflation in subsequent periods.

- Money supply plays a role in the transmission mechanism of policy, but is not a policy instrument nor a target, as the central bank has an inflation target, and uses monetary aggregates as indicators only.

- There is a positive relationship between monetary aggregates and the general level of prices. - “Monetary growth persistently in excess of that warranted by growth in the real economy will inevitably be the reflection of an interest rate policy that is inconsistent with stable inflation. So control of inflation always ultimately implies control of the monetary growth rate. However, the relationship between the monetary aggregates and nominal GDP ..appears to be insufficiently stable (partly owing to financial innovation) for the monetary aggregates to provide a robust indicator of likely future inflation developments in the near term.”

– Examples include declines in bank lending caused by losses of capital on bad loans: a credit crunch.

Samurai Issues from October 2008 to 2015